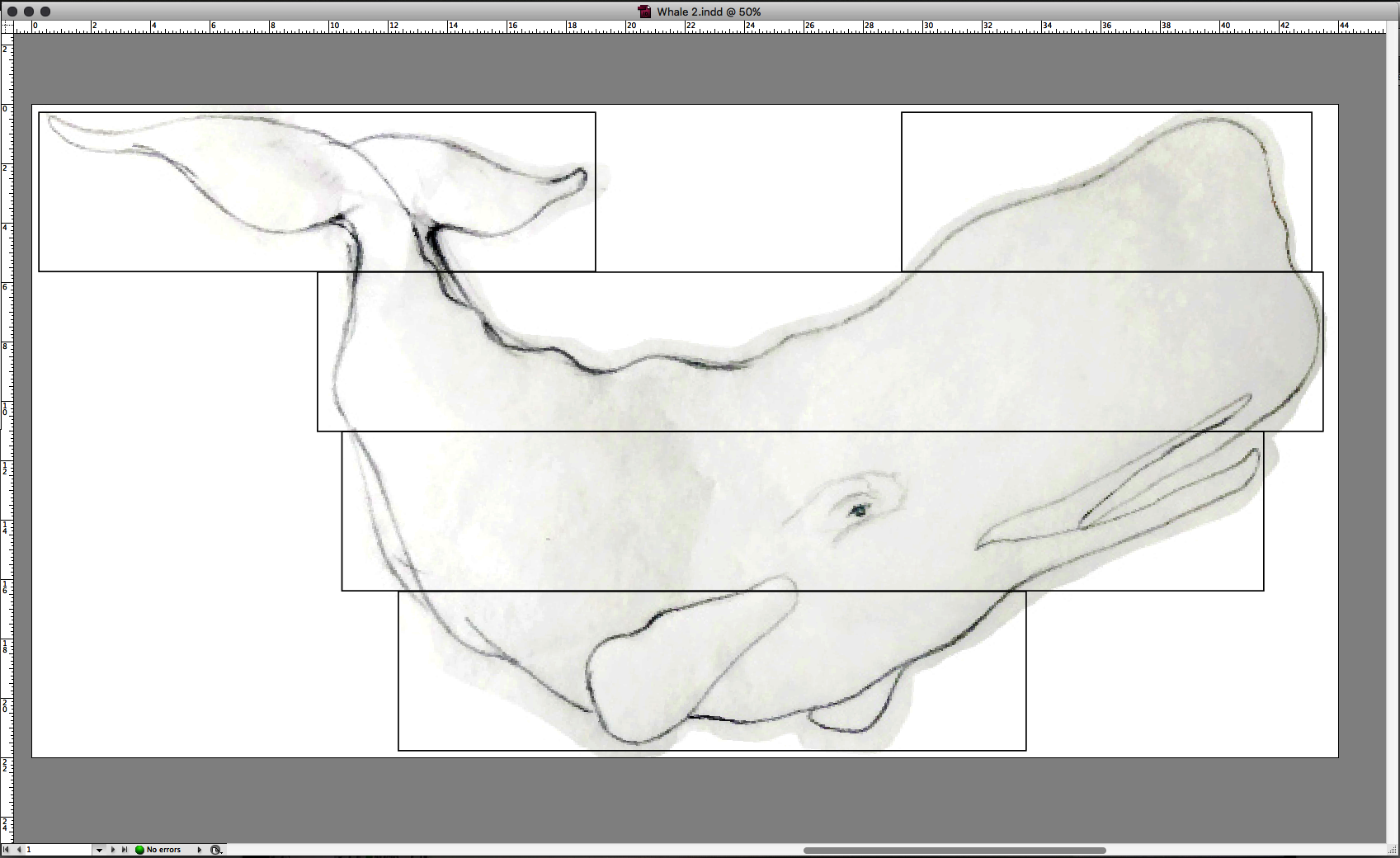

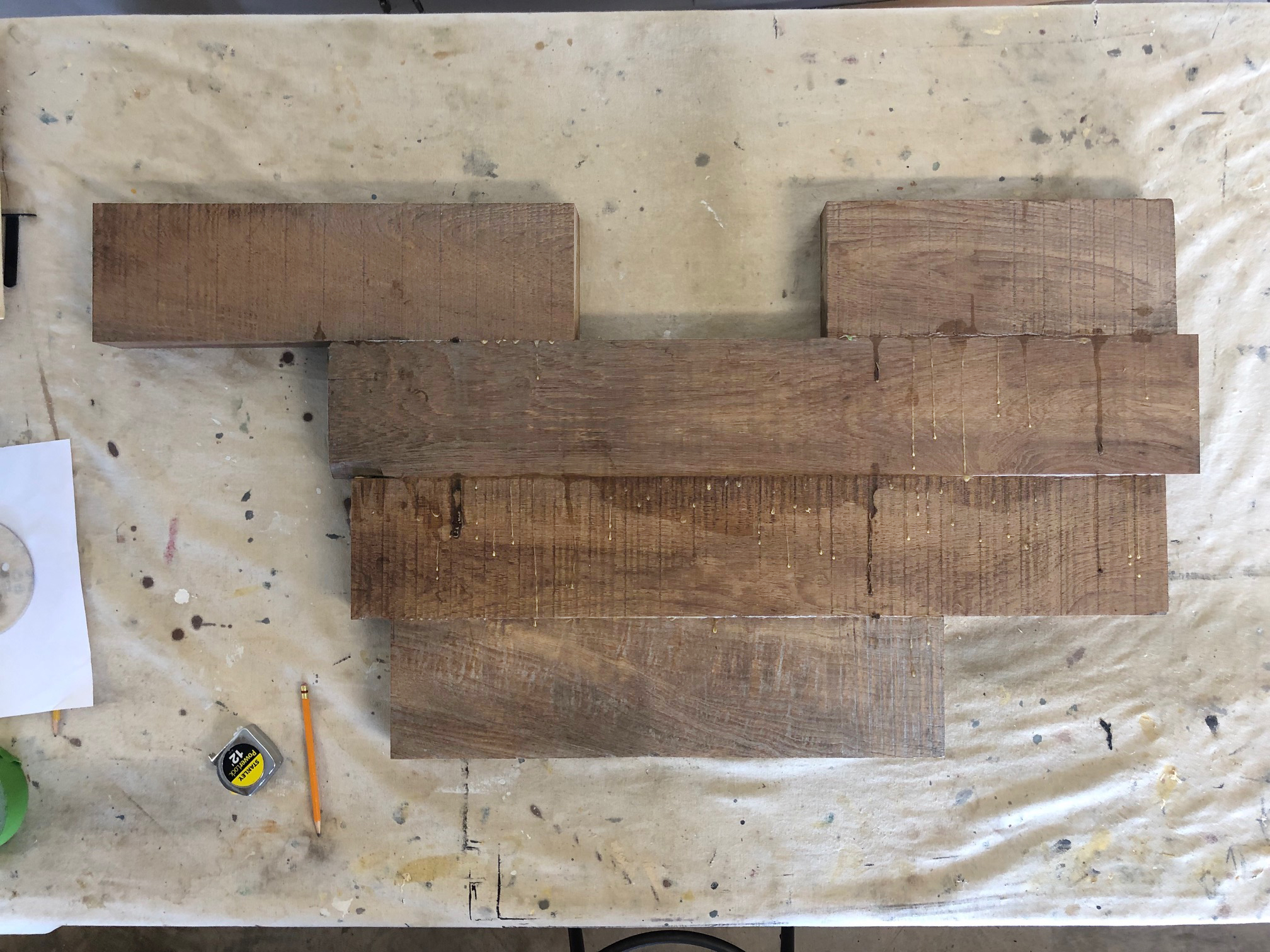

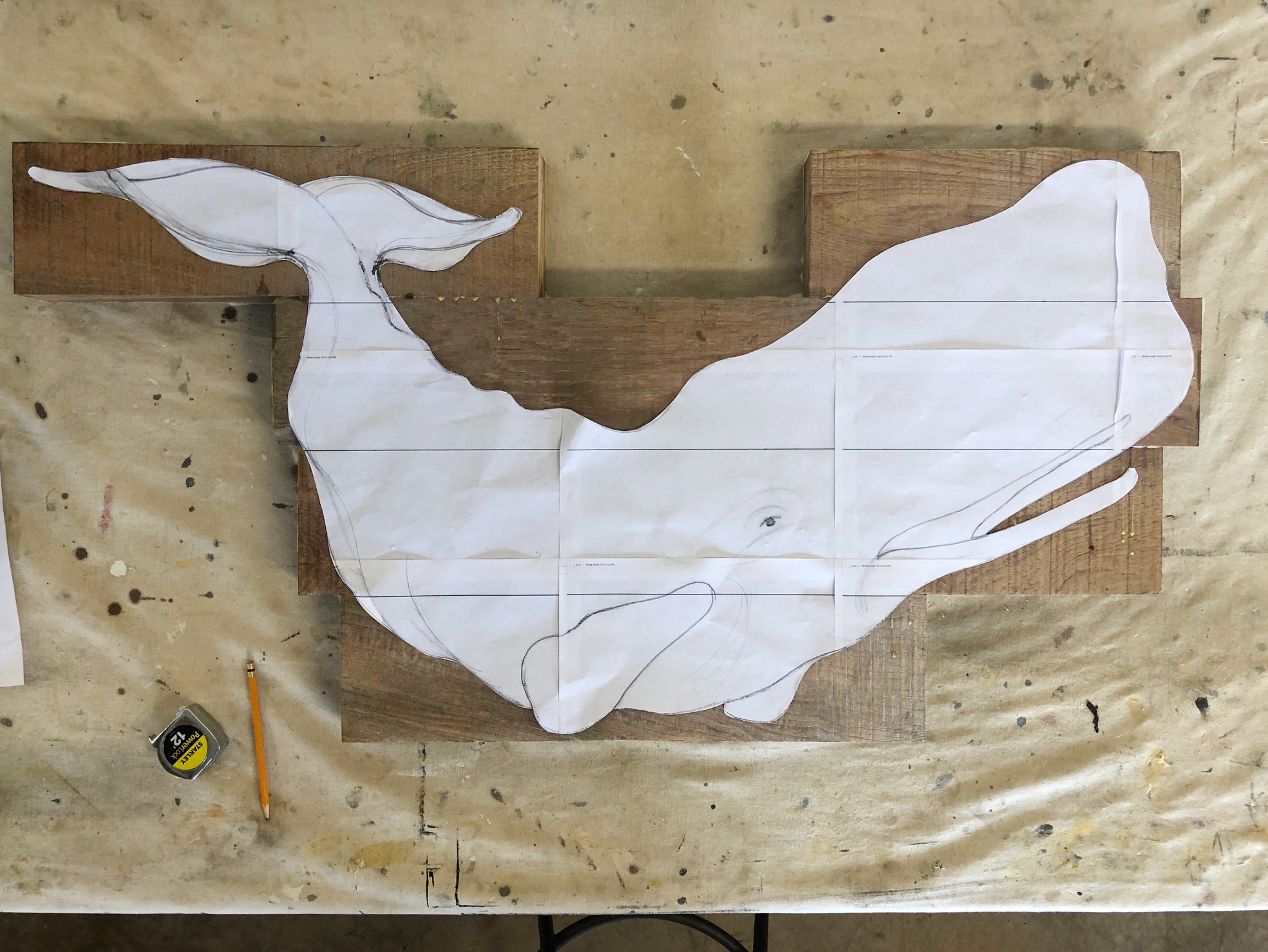

At six feet long and rich in detail and period accuracy, this wall hanging involved 1800s research and a touch of time-travel imagination. Our goal—using a folklore-inspired whale shape, early signwriter’s lettering styles, and a weathered finish—was to create something convincing and ultra-authentic to satisfy the museum curators who asked us to collaborate on an exhibit. We envisioned this sign hanging on the front of a Nantucket or New Bedford mercantile when the household need for whale oil was as vital as milk and bread. For centuries, sperm whale oil, also known as spermaceti, lit homes and cities around the world with its ultra-bright, odorless burn. It lubricated the Industrial Revolution until the 1859 discovery of Pennsylvania crude oil, which abruptly ended the whale oil industry and its centuries-old way of life for whaling communities worldwide.

To show how today’s artists celebrate historic American folk art signs, this original Nutmegger Workshop design and carving, along with another work from fellow sign artist Dinardo Vintage, was part of the Taverns to Trades: American Folk Art Signs exhibit at the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit, MA, from September 17–December 21, 2025.

This museum-quality piece is for sale.

A few scraps of inspiration gathered online.